Toki Pona

Toki seme?

Toki pona is a constructed language by jan Sonja. It is designed to be simple to use, with fewer than 150 words and minimal grammar. It is neither a pidgin, nor a cant, but a fully fledged language. It was designed to simplify communication and thought by reducing concepts to their essence.

You might assume that a language like this is either severely limited or incredibly verbose, but neither is the case. It has its own wiki with a few thousand articles on all sorts of complex matters.

Almost all languages have phonetics which can’t be pronounced by people from at least some linguistic backgrounds. Toki pona has been designed to be pronounceable by everyone, so it skips a few consonants and has strict rules for its syllables.

Since toki pona is constructed, its words have to be taken from somewhere. Most words are adopted from various languages: “perkele” is a Finish profanity, “pakala” means “to break something” in toki pona. It’s also what you’d exclaim if something heavy falls on your foot.

Nimi

Words in toki pona don’t have precise meanings like in most languages, but rather describe broad concepts. Take, for example, the word telo: it describes the concept of a fluid. As a noun, it can be used for “ocean”, “orange juice” or “sweat”, among others. What it means in a particular context depends on that context. If I offer you a telo, I’m probably not talking about rain. To be clear: words in toki pona aren’t ambiguous, they’re better defined than in most languages, it’s just that their definition is vague, an important distinction.

Additional context can be provided by adjectives, a telo might be orange juice or a tea, but a yellow telo is much more specific. Beginners often use those additional specifiers excessively, leading to long and convoluted sentences. As you become more familiar with the language, your sentences become more succinct. Toki pona words are rarely longer than two or three syllables. I did a few comparisons, my sentences have roughly the same length in both English and toki pona, while conveying the same meaning.

Words in toki pona are not restricted to a single lexical category, instead they can be used to fill all roles. If your shirt is telo, it is wet, and if you telo your plants, you water them. A telo animal lives in the sea and a telo day makes you wish you brought an umbrella.

Originally, the language had 120 words, but the community filled a few gaps. Wikipedia lists 137 essential words, depending on who you ask it might be a few more or less. Translations depend on context, so you can’t just look them up 1:1. On top of that, many people have their own favourites. Some call a computer an ilo sona (“tool of knowledge”), others prefer ilo pi sitelen soweli (“cat picture device”), I personally use poki nanpa (“number box”). This can make it difficult for beginners, but learning the words individually and then assembling the translations yourself is the true way to toki pona.

Toki pona is very literal, so it doesn’t do well with idioms. Descriptions are primarily about simple, observable properties, rather than abstract concepts or values. This makes the language more accessible for people from different cultural backgrounds, as cultural references are somewhat culled by being translated. Everything expressed in toki pona is implicitly subjective, if someone calls you a jan pona (“good person”), that means you’re their friend.

Nasin toki

The vocabulary of toki pona is simple, its grammar is simpler still. In the previous chapter I described how a word can fill many roles, figuring out if telo is a noun or a verb is crucial.

Toki pona makes this very easy. A regular sentence has a subject, a verb (or verb-like adjective) and (optionally) an object. Their separation is indicated by dedicated words: li marks the separation of subject and verb, and e marks the separation of verb and object. The word soweli describes all sorts of mammals, so “The cat is wet.” becomes “soweli li telo”. A more literal translation would be “The mammal is being wet”. A kasi is a plant, so “soweli li telo e kasi” means “The cat is making the plants wet”.

Adjectives and adverbs work by adding them after their noun/verb: soweli telo is a wet cat. In english you put them in the front, in toki pona you put them at the back.

Toki pona doesn’t have gender, tense, inflection or grammatical numbers. This keeps the language simple. If you want to explicitly express that something happens at a particular time, you express the time as a condition (indicated by la) and follow it with a regular sentence:

tempo kama la, soweli li telo.

translates to

When it is the coming time, the mammal is wet. / The cat will be wet.

These conditions aren’t specifically for time, but rather a general feature of the language:

mi la, soweli li telo.

uses mi (first person, I/we) as a condition, indicating that what follows is true under the condition “me”:

If you accept my perspective, the mammal is wet. / In my opinion, the cat is wet.

If you want to explicitly refer to one cat, you can use wan, which is the concept of “a single thing”, here used as adjective:

soweli wan li telo.

A singular mammal is wet. / The cat is wet.

Usually you’d skip the wan, since its given by context, but it can be useful if there’s multiple cats around. Languages generally provide these informations implicitly as part of their grammar. In toki pona, this information is omitted unless it is relevant, in which case it is explicitly provided.

There’s a bit more grammar, notably questions, commands and multiple distinct subjects/objects. This is article isn’t meant to be a complete specification of the language, but if you made it this far, you’ve understood the bulk of its grammar.

Sitelen pona

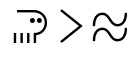

You can use the latin alphabet to write toki pona, but given that it has very few words, it makes sense to write entire words as single glyphs. Sitelen pona is a set of glyphs for toki pona which mostly uses pictograms that represent the word’s meaning.

Note how the first glyph has two eyes and four legs (like a mammal) and the last one has two wavy lines (like water). Sitelen pona has a few glyphs which are a bit tricky to write, and some of which look similar to others. Personally, I prefer the slightly adapted sitelen pona pona, which fixes some of those issues. There’s many other writing systems as well. Sitelen sitelen is a more artistic (albeit less practical) variation.

Sona kama

I always struggled with languages in school, so I was sceptical about picking up toki pona. However, I was making quick progress with very little effort from the beginning. With just 15 minutes a day, I was able to:

- write and read toki pona within a single month

- speak toki pona slowly within a month and a half

- speak toki pona fluently within two months

It took me another two weeks to pick up sitelen pona (pona) after that.

Learning toki pona is a lot of fun, and by the end you’ll know a whole new language! It’s perfect for secret journals or making fun of people with your friends.

There are many resources for learning toki pona. If reading a physical book is your thing, there’s pu by jan Sonja. I mainly learned toki pona by jan Misalis toki pona lessons on youtube. There’s still some lessons missing, but you can follow up with his old series. If you want to click around, there’s jan Pije’s wikibooks lessons. If you prefer to talk to people, there’s the ma pona Discord community.

This is just a brief list of resources, I’m sure you’ll be able to find what you’re looking for with a quick web search.

o pona! mi tawa.